PhoenixForCynicalCurmudgeons

Introduction

Unfinished.

This is an attempt to wrap my head around using the Phoenix web framework for a small project. However, it got too long so I broke it into two parts. This is part 2 and just talks about Phoenix itself, part 1 is ElixirForCynicalCurmudgeons and talks about the Elixir language. I realized that I have a number of attitude issues that make Phoenix hard to start getting into, so I’m going to attempt to write about it in a way that makes sense to me.

My issues are:

- I don’t actually know Erlang too well in practice

- I don’t actually know web programming too well in practice

- I don’t actually like web programming much

- I’ve spent the last 10 years being the go-to person to fix every random technical thing that could screw up, and am thus something of a pessimist and a control freak

- The world is burning down around us and none of us can do anything about it

So, if you share some of these issues, maybe this doc will be useful to you. This will not teach you Elixir or Phoenix, but it may help you figure out how to think about Elixir. This is a supplement to the official docs, not a replacement, so it won’t try to cover the things that those docs explain well.

Disclaimer: As far as I know this is correct, but there’s probably details I’m missing or misinterpreting. Don’t take this as gospel. I am not an expert, I am merely a determined idiot.

Last updated in August 2023. It uses Elixir 1.14, Erlang/OTP 25 and Phoenix 1.7.7.

What were we doing? Oh right, Phoenix

Great, we’ve talked about Elixir a bunch, now let’s get to Phoenix! We need a test application to talk about, so I will try to make a basic wiki. I’ll call it Otter, just ’cause.

Phoenix is a framework for building web application backends – and integrating them with frontends, as well. There’s usually two broad types of software you will tend to see for this sort of thing, minimal or maximal. The minimal frameworks like Flask, Go’s stdlib server, etc start you with almost nothing and let you build up incrementally, and the maximal ones like Django, Rails, etc will deluge you in all the pieces you will ever need. Phoenix is definitely the “deluge” type; when you create a default Phoenix project it gives you a database management system, templating engine, live reloading including browser push, esbuild, telemetry, language translations, authentication, responsive web frontend integration with websockets, asset management, what feels like ten million plugins…

I don’t like this. I mostly deal with the hype and churn of web development by avoiding it as much as humanly possible, which has turned out pretty well for me all in all. But being able to sling webs is pretty useful from time to time, so having at least a basic grasp of web backends is necessary. And I spent long enough developing and maintaining a new application in Django to accept the truth that, sooner or later, sooner or later you will probably need most of the pieces that it deluges you with.

Phoenix is built atop an Erlang web server called Cowboy, and Cowboy uses a lot of the same plugin-y technology of Phoenix, so if you want a minimal web app framework you might be tempted to just use Cowboy. I will probably try this out sooner or later, but the people on the Elixir Discord server discouraged this approach, calling it “the most recurring beginner miscomprehension”. It sounds like Cowboy is pretty low-level and not super convenient, while Phoenix is pretty streamline-able, so it’s a lot easier to snip the unnecessary things out of Phoenix than to add the necessary things to Cowboy. Fine, I’ll trust them to know what they’re talking about and just use Phoenix. This time.

Bird’s Eye View

The official Phoenix guide does a pretty good job of explaining the details and various fiddly bits and bobs. Nothing wrong with that. But I’m an inductive thinker: I work best when I start with the big picture and then focus down on the details. So I want to give the high-level outline that the official docs lack, and let those fill in the details for me.

Stirring shit up

Phoenix’s “entry point” is a program called mix, which

is more or less the Elixir equivalent of cargo or

go or whatever. It’s a smart build and packaging system,

but unlike cargo or go it seems optimized for

you to build extensions/plugins to it called “tasks” which perform

particular operations or start your program in a particular state. In

Rust if you have a tool that is commonly used along with your program’s

source code you might bother writing a cargo

plugin so you can just type cargo do-thingy, but it’s a

relatively high bar before it’s worth it. In mix this seems

a lot more common, and installing Phoenix loads a pile more tasks for

you to use. (They really missed out on the chance to call them “mixins”;

c’mon guys!) Annoyingly mix and its various tasks tend not

to use Unix-conventional command line syntax, but they do provide handy

docs and a consistent user interface:

$ mix help

mix # Runs the default task (current: "mix run")

mix app.config # Configures all registered apps

mix app.start # Starts all registered apps

mix app.tree # Prints the application tree

mix archive # Lists installed archives

mix archive.build # Archives this project into a .ez file

mix archive.install # Installs an archive locally

mix archive.uninstall # Uninstalls archives

mix clean # Deletes generated application files

mix cmd # Executes the given command

mix compile # Compiles source files

mix deps # Lists dependencies and their status

mix deps.clean # Deletes the given dependencies' files

mix deps.compile # Compiles dependencies

mix deps.get # Gets all out of date dependencies

mix deps.tree # Prints the dependency tree

mix deps.unlock # Unlocks the given dependencies

mix deps.update # Updates the given dependencies

mix do # Executes the tasks separated by plus

mix escript # Lists installed escripts

mix escript.build # Builds an escript for the project

mix escript.install # Installs an escript locally

mix escript.uninstall # Uninstalls escripts

mix eval # Evaluates the given code

mix format # Formats the given files/patterns

mix help # Prints help information for tasks

mix hex # Prints Hex help information

mix hex.audit # Shows retired Hex deps for the current project

mix hex.build # Builds a new package version locally

mix hex.config # Reads, updates or deletes local Hex config

mix hex.docs # Fetches or opens documentation of a package

mix hex.info # Prints Hex information

mix hex.organization # Manages Hex.pm organizations

mix hex.outdated # Shows outdated Hex deps for the current project

mix hex.owner # Manages Hex package ownership

mix hex.package # Fetches or diffs packages

mix hex.publish # Publishes a new package version

mix hex.registry # Manages local Hex registries

mix hex.repo # Manages Hex repositories

mix hex.retire # Retires a package version

mix hex.search # Searches for package names

mix hex.sponsor # Show Hex packages accepting sponsorships

mix hex.user # Manages your Hex user account

mix loadconfig # Loads and persists the given configuration

mix local # Lists local tasks

mix local.hex # Installs Hex locally

mix local.phx # Updates the Phoenix project generator locally

mix local.public_keys # Manages public keys

mix local.rebar # Installs Rebar locally

mix new # Creates a new Elixir project

mix phx.new # Creates a new Phoenix v1.7.7 application

mix phx.new.ecto # Creates a new Ecto project within an umbrella project

mix phx.new.web # Creates a new Phoenix web project within an umbrella project

mix profile.cprof # Profiles the given file or expression with cprof

mix profile.eprof # Profiles the given file or expression with eprof

mix profile.fprof # Profiles the given file or expression with fprof

mix release # Assembles a self-contained release

mix release.init # Generates sample files for releases

mix run # Runs the current application

...and more...Running mix help something will show more detailed docs

for that particular task. Not mix something --help. The

help docs for various tasks tend to be either painfully brief of

overwhelmingly long, but oh well. Let’s look at the most common and/or

least self-explanatory tasks:

compile– Compile your code. Not usually necessary, running stuff compiles it anyway if necessary.run– Start the current OTP application, along with any application dependencies it has. You can also pass it a script to execute, command line args, code to eval, etc.test– Run unit tests. “This task starts the current application, loads uptest/test_helper.exsand then runs all files matching thetest/**/*_test.exspattern in parallel.”clean– Nuke your application’s compiled files in the_builddir. Leaves compiled dependencies unless you specify--depsas well.release– Builds a redistributable-ish binary you can schlep to another computer and run. This functionality looks useful but also full of all the gotcha’s that distributing binaries always has, so I won’t worry about it now.iex -S mix– Starts aniexREPL with the current directory’s project and stuff already compiled and loaded.

A basic Phoenix server is wrapped up in an OTP application. You HAVE

read the

various mountains of excessively

detailed OTP

documentation, right?

And fully absorbed every detail and

nuance? Yeah me neither, though I keep nibbling away at it as much as I

can. Suffice to say, an “OTP application” is one or more Erlang

processes, all the other processes they need to run sanely, a

supervision policy, an RPC and discovery protocol, etc. Basically OTP

takes care of what, for any other server running on Linux, you would

normally do with some systemd service definitions, a bevy

of config files, likely some monitoring software, maybe a few Ansible

scripts, and probably other things I’m not aware of. It just does it

probably better, and totally more stylishly.

Then there’s a bunch of things nested beneath various toplevel commands. You can figure them out in your own time, I’ll highlight the main toplevel things:

app– Does stuff with the OTP applications that make up your project. Notably,mix app.treeprints out all the applications and such that go into actually making the program run when you start it.hex– hex.pm is the package repository for Elixir and Erlang, like crates.io for Rust. Unlike Rust, it is not as tightly-coupled to the build tool for the language, it’s just a plugin tomix. AFAICTmixautomatically useshexfor dependency resolution anyway, so idk why they’re separate subsystems, but they are.ecto– Entry point to mess with your project’s database config, such as creating and applying migrationsphx– Entry point to mess with Phoenix shortcuts, such as adding a schema or printing out what routes exist. Notably, runningmix phx.serverruns your program.

There’s a few sneaky things that come out of this. For example,

running mix app.start for some reason appears to start and

then exit, you have to run mix phx.server – I’m sure

there’s a reason but idk what it is. But then running

iex -S mix phx.server starts your server running,

and opens a REPL in its environment, which seems pretty

handy.

mix is controlled by the mix.exs script

that has some arbitrary Elixir code in it. This is mostly actually OTP

application stuff, nothing Phoenix specific, so I’m not going to go too

deep into it. All Phoenix fills out for you in it is the list of

dependencies, some build related stuff, and the aliases

function which adds extra mix shortcuts for you. So for

example running mix test will actually run one of those

aliases which does

mix ecto.create --quiet; mix ecto.migrate --quiet; mix test.

This again comes under “things you will want anyway”.

mix has options for various run environments, by default

dev, prod and test. You set which

one with the MIX_ENV environment variable; the default is

dev but if you do MIX_ENV=prod mix phx.server

it will start in prod. Presumably MIX_ENV is

set to test when running unit tests? This lets you start

different configurations, as we’ll see; for example Phoenix gives you a

bunch of extra debugging and live-reloading stuff when you run in

dev mode.

Actual Phoenix stuff finally

Phoenix provides a mix task phx.new to

generate the new project template, so doing

mix help phx.new will get you a list of useful options for

configuring how your project is set up. There’s something about an

“umbrella project”, which I’m not going to try to worry about, and

there’s a --database option that lets you choose which

database adapter to use. It defaults to postgres, for this

I’ll set it to sqlite3.

After that there’s a bunch of --no-* options for

generating projects with various bits of the deluge snipped out. Let’s

take a look at each in turn:

--no-assets- “equivalent to--no-esbuildand--no-tailwind.” Pretty self-explanatory, we’ll get to each of those in turn.--no-dashboard- “do not include Phoenix.LiveDashboard.” “LiveDashboard” is a debugging and monitoring dashboard. TODO: Investigate more.--no-ecto- “do not generate Ecto files.” Ecto is a database wrapper and query generator, somewhat similar to SQLAlchemy in Python or LINQ in C# or Diesel in Rust. It also handles database migrations. Worth keeping if you’re using a database.--no-esbuild- “do not include esbuild dependencies and assets.” ESBuild is a Javascript compiler/bundler, probably one of the less shitty ones according to what I’ve been told. Phoenix appears to use it to handle assets in general, so even if you have nothing to do with JS you can use it to do things like transform/minify CSS, keep paths to assets--no-gettext- “do not generate gettext files.” Gettext is a library to handle translations to different languages, essentially by letting you make a file full of template strings for each language. Probably worth keeping and I’ll probably never get around to using it.--no-html- “do not generate HTML views”. Gives you some starter HTML templates. Worth keeping if you’re not making a purely API-based server.--no-live- “comment out LiveView socket setup in assets/js/app.js.” LiveView appears to be a way to shuffle Elixir messages to a web frontend via Websocket, the same way you would shuffle them between BEAM processes via channels. It appears to be a nontrivial chunk of JS at 170 kb compressed, but the possibilities are intriguing. I’d still leave it off unless I really wanted that kind of interactivity though.--no-mailer- “do not generate Swoosh mailer files.” Swoosh generates and sends emails for you, via SMTP, or other services with API’s such as Mailgun. Enable if you want your service to send password reset emails.--no-tailwind- “do not include tailwind dependencies and assets.” TailwindCSS is a library for making CSS shinier. Never used it; to me it appears to be the Next Bootstrap, and thus mostly uninteresting. Still, people seem to like it. This will also download and install “heroicons”, dumping about 8 megabytes of random SVG’s into yourassets/folder. So, you know, be aware of that when you check your project into git.

So really, these options fall into pretty sensible categories: “if it’s not there I’ll need to invent it” (ecto, esbuild, html), “I will never use it but I probably should” (swoosh, gettext), and “frontend people will enjoy this but I don’t” (tailwind, liveview). And the dashboard, which is intriguing. None of these do anything particularly magical, from playing around with them each one just adds a few items to your deps list, adds some extra template files for you to flesh out, and fiddles around with build setup as necessary.

So create your project with the parameters you want. For me this is

mix phx.new otter --database sqlite3 --no-tailwind. I might

want to play around with liveview so I’m leaving it in for now, though

I’ll probably rip it out later. It will download some deps and build

some stuff, and then you should have a project structure something like

this slightly-abbreviated one:

otter/

├── .gitignore

├── assets

│ ├── js

│ └── vendor

├── _build

├── config

│ ├── config.exs

│ ├── dev.exs

│ ├── prod.exs

│ ├── runtime.exs

│ └── test.exs

├── deps

├── lib

│ ├── otter

│ ├── otter.ex

│ ├── otter_web

│ └── otter_web.ex

├── mix.exs

├── mix.lock

├── priv

│ ├── gettext

│ ├── repo

│ └── static

├── README.md

└── test

├── otter_web

├── support

└── test_helper.exsThis looks like a lot but honestly isn’t. The biggest and most

complicated parts are _build and deps, which

are 100% ignorable. They’re just where mix puts build

artifacts and stores downloaded source for dependencies. The provided

.gitignore already ignores them. There’s more subdirs under

assets/* and priv/* that I will talk about

when they matter. lib/otter/ and

lib/otter_web/ just have a bit of template code.

Other than that we have:

assets– Input assets, such as CSS templates or non-minified JS. These get fed intoesbuildand output intopriv/static/assets; you can see theesbuildcommand line inconfig/config.exs.config– Both build and application config, and the differences between them.dev.exs,prod.exsandtest.exsconfigure what happens when you build for development or production, or run unit tests. For example,dev.exsenables a pile of extra logging,test.exsmakes it use a separate database just for unit tests, etc. Then there’sconfig.exswhich seems to be mainly for configuring subcomponents like logging and esbuild, andruntime.exswhich appears to be where you stick the stuff to do application configuration such as loading your database path or transient secrets from env vars.lib– This is where your actual code goes.otteris whatever non-web operations you want to actually perform,otter_webis the web-y bits that are invoked when HTTP connections actually hit your server. The actual entry point islib/otter/otter.ex, which defines an OTP application like any other and which specifies the sub-applications to start with it, includingOtterWeb. The idea is that theotterapplication handles your business logic andotter_webonly does HTTP stuff.priv– ???test– Unit tests. There will be a few already generated for you, with plenty of comments.mix.exs– Yourmixbuild script.mix.lock– Your lockfile, generated and maintained bymix.

On to actual Phoenix stuff

Whew, that was a fuckload, wasn’t it? This is what I was talking about when I used the word “deluge”. It all makes sense, but there’s just a lot of stuff there to absorb and none of it works quite like anything else you’ve ever touched. The Elixir/Erlang/BEAM/OTP/OMGWTFBBQ ecosystem tends to be like that. It was developed mostly divorced from the Unix-y world we now call “normal”, so all the conventions are different and foreign. I’ve dealt with the ugly edges of Unix enough that this is difficult to deal with, but also not unappealing.

Phoenix has a several separate stages of processing that come together into a chain. They are:

- Endpoints

- Routers

- Controllers

- Components

An incoming HTTP request basically goes down through this list in order. You have one Endpoint that every request starts at, which handles stuff you want to do for every single request like logging, routing static path requests to static assets, then handing the request off to your Router. It’s pretty simple. The Router is just like routing in any HTTP backend server: it looks at the incoming request and, based on its path, method, or other properties like cookies or sessions or whatever, and decides what function to send it to. You can define scopes and nest them to build hierarchies of paths out of sub-routers, and Phoenix has some shortcuts for generating a REST-y object API based off of data, and a bunch more features that look like they’d be a pain in the ass to write yourself. A Controller is just the function that takes a request and Does Something with it, such as render and return data. Components are functions that actually produce the data to return, and can be nested/combined together in various ways. For example, you can have a component that renders a HTML page using a template (using Phoenix’s built-in template language called HEEx), and have the template contain a call another component that generates a table, then have that component call another one that generates each row in the table. So all in all, it’s not particularly complicated or crazy.

Let’s talk about “plugs” though, because most of these things are

actually built out of chains of plugs. Plugs are what other HTTP servers

generally call “middleware”, which is just a function that takes a

request and returns a response, designed in such a way that you can

chain bunches of them together into “pipelines” of decoupled

functionality. Apparently the only real difference between plugs and the

middleware of most other servers is that plugs both accept and return a

Plug.Conn object, which represents both request and

response. Metadata added by the plugs and the response you want to send

are both just hung off the Conn object, so you can build

responses incrementally, short-circuit when an error happens and return

a partial response without having to go through all the other plugs,

that sort of thing. I have no idea whether this is a good idea or not, I

just don’t have enough experience with different servers. But it means

that a plug is very simple: it is a function that takes a

Conn and an assoc list of options, modifies the

Conn, and returns it. You can also make a module that is a

plug, which has a function with the same signature plus an

init(defaults) function to it that can initialize some

state if it needs to. There’s about ten million predefined

plugs for doing about anything you could wish for.

As mentioned, plugs are composed into “pipelines”, which have a name

and are just a list of plugs that a connection zips through in order. So

for example the Phoenix tutorial constructs a :browser

pipeline that accepts Content-Type: text/html and handles

sessions, XSRF protection etc and an :api pipeline that

accepts JSON and hangs them off of different router paths, say

/ and /api. Something sends a GET

to example.com/whatever it gets sent through the

:browser pipeline and then hits the Controller

matching /whatever, something sends a GET to

example.com/api/whatever it gets sent through the

:api pipeline and hits the Controller the

router specifies for /api/whatever.

So this gives us a good idea for how to add or remove broad features from Phoenix, like LiveView or the debugging dashboard: Just alter the appropriate lists of plugs. You probably need to know a bit about which plugs you need to touch and how they interact, but well, that’s always true. But yes, it appears that nothing in Phoenix’s deluge-of-shiny-features is actually hardcoded in, they’re just plugs that are slotted in by the project-init task.

Apparently Controller’s are actually just plugs as well,

but I tried to figure out how they work in the example project and ended

up reading three-layer-deep macros that appeared to exist purely to

avoid writing the same four lines of import’s in two

different places. Hmmmmm.

Case study

Let’s look at the crazy-bones Phoenix DSL snippet from the previous tutorial and take it apart bit by bit:

defmodule OtterWeb.Router do

use OtterWeb, :router

pipeline :browser do

plug :accepts, ["html"]

plug :fetch_session

plug :fetch_live_flash

plug :put_root_layout, html: {OtterWeb.Layouts, :root}

plug :protect_from_forgery

plug :put_secure_browser_headers

end

pipeline :api do

plug :accepts, ["json"]

end

scope "/", OtterWeb do

pipe_through :browser

get "/", PageController, :home

end

scope "/api", OtterWeb do

pipe_through :api

end

if Application.compile_env(:otter, :dev_routes) do

import Phoenix.LiveDashboard.Router

scope "/dev" do

pipe_through :browser

live_dashboard "/dashboard", metrics: OtterWeb.Telemetry

forward "/mailbox", Plug.Swoosh.MailboxPreview

end

end

endOk, we’re defining module OtterWeb.Router, so this is

our router entry point. How does control flow actually get here though?

OTP is so decoupled and Phoenix is so macro-heavy that this is not

particularly obvious, which is one of the things about it that

cheesegrater’s my brain a little bit when trying to understand how

everything fits together. But with a little work we can hunt down where

OtterWeb.Router is actually used, it’s the last plug

defined in the chain of plugs in OtterWeb.Endpoint, and

OtterWeb.Endpoint is listed in the list of OTP applications

in lib/otter/application.ex that need to be running for it

to consider the otter application to be successfully

running. So we just need to tell BEAM “start the otter

application” and it also starts all the sub-pieces of it such as the

database interface, pubsub, and actual HTTP server. And sensibly

monitors them and restarts them appropriately when they or their

dependencies fail, which I’ve never really been able to get

systemd to do satisfactorily.

Right, the first line is use OtterWeb, :router so right

off the bat we’re in Macro Land. We’ll see what’s actually going on in a

second, but just look at the shape of the file again and think

about how you’d write it in some other language. I’ve mostly written web

services in Python or Rust and in both you tend to either have some

decorators or macros to Arrange Things Nicely, or you very explicitly

wire together data structures into something that describes your web

server and feed it into a run function. I’d expect to have

an actual list of plugs, and I’d expect each scope full of

routes to be some structure that contains the string and an actual

function object to call. Nope, it’s just the module and an atom, which

is the name of the function in that module to call. It’s very nice and

declarative-looking, but a little bewildering… I guess it’s just

creating that structure for us and doing a dynamic dispatch on the

function’s name? Feels a little inefficient, but I guess it’s fine?

Remember, we’re in Macro Land here! Up is down, black is white, and afaict it isn’t constructing a data structure that stores the name of the function and calls it for you, it’s constructing a pattern match block that calls the function directly. And if there’s one thing in BEAM that’s always in the hot path and will be first to get optimized, it’s pattern matching. The docs even mention that if you use a route or function name that doesn’t exist, you’ll get a pattern match failure. Elixir is a Lisp, and Phoenix is not really a web server, it’s a DSL for writing web servers.

So let’s actually go through this, from the top again. We

define a pipeline of plugs called :browser, and fill it

with everything we’d probably want to do to a browser request: make sure

the input’s requested content-type is HTML, handle sessions and whatever

nonsense a “live flash” is, tell it to find our HTML templates via

OtterWeb.Layouts, and some security stuff that I should

probably look up the docs for. Then we define another pipeline of plugs

called :api that does none of that, just makes sure that

the request’s content-type is JSON.

Then we have a couple scope blocks which define our

actual routes. scope "/", OtterWeb do defines a route

starting from "/" and tells it that all the modules and

such are under the OtterWeb module. We write

pipe_through :browser to hang our list of

:browser plugs off of any endpoint in the scope, then

get "/", PageController, :home connects the route

"/" to the controller

OtterWeb.PageController.home(). So any GET /

request will ultimately end up calling

OtterWeb.PageController.home(), which currently just

renders an HTML template and returns it. As is typical with such things,

there is a whole pattern-matching sub-language in the route

specification, and it’s pretty sweet, but the Phoenix docs cover that

fine so I won’t. Then we also have a scope for "/api"

routes, but don’t actually define anything in it yet.

Then we have an if expression right in the toplevel

module, which is apparently okay I and just generates code? Learn

something new every day! But it just enables the LiveDashboard feature

and the email monitor if we’re running in dev mode and

leaves it out otherwise. It does

import Phoenix.LiveDashboard.Router, but it’s

import and not use so nothing too

crazy is happening there, they’re just calling

Phoenix.LiveDashboard.Router.live_dashboard beneath because

Phoenix devs appear immune to writing out an absolute module path, even

once. forward forwards all requests on to another plug

instead of filtering for GET or POST or

something like that.

But let’s look at that weird if again; it’s

if Application.compile_env(:otter, :dev_routes). What the

heck is :dev_routes? I don’t see that shit mentioned

anywhere in the Phoenix docs… but if we search our project dir

for it we see that config/dev.exs contains the line

config :otter, dev_routes: true. It’s just a variable set

in our dev-build config. Startlingly sensible!

So… yeah. Phoenix looks like a lot, but it isn’t actually so crazy, it just puts a lot of work into defining a DSL for you to write a webserver in. But since pretty much every single statement in that DSL takes 0 or more args and then an assoc list, the same way as any other Elixir structure, there’s really not very much actual syntax that goes into it. The DSL is just Elixir with new keywords. And it’s not a matter of Syntax Sugar For Making Programming Less Scary, either; it actually implements a lot of compile-time safety as well, as we will see in the next few bits. Plus I suspect it does most of its actual data-manipulation stuff at compile-time, and thus compiles down to very tight code. I don’t know for sure, but wouldn’t be surprised.

Components and templates

Despite myself, I actually kinda like generating HTML. It’s a guilty pleasure, but it’s very satisfying to have some pieces of random string fragments all come together automatically into a complicated interlocking page.

A Component is, at its heart, just a function that takes some data and returns a HEEx template.

Other cool shit

There’s a reader macro for writing routes, so if you change or

misspell a route in your code or templates, instead of breaking at

runtime it will warn you at compile time that you never defined a route

named /api/thign. That’s a type of compile-time that you

usually don’t get from Rust, made possible ’cause Phoenix can introspect

on the code its macros generate. In theory you can do something like

that in Rust by slinging macros as well, but it sucks.

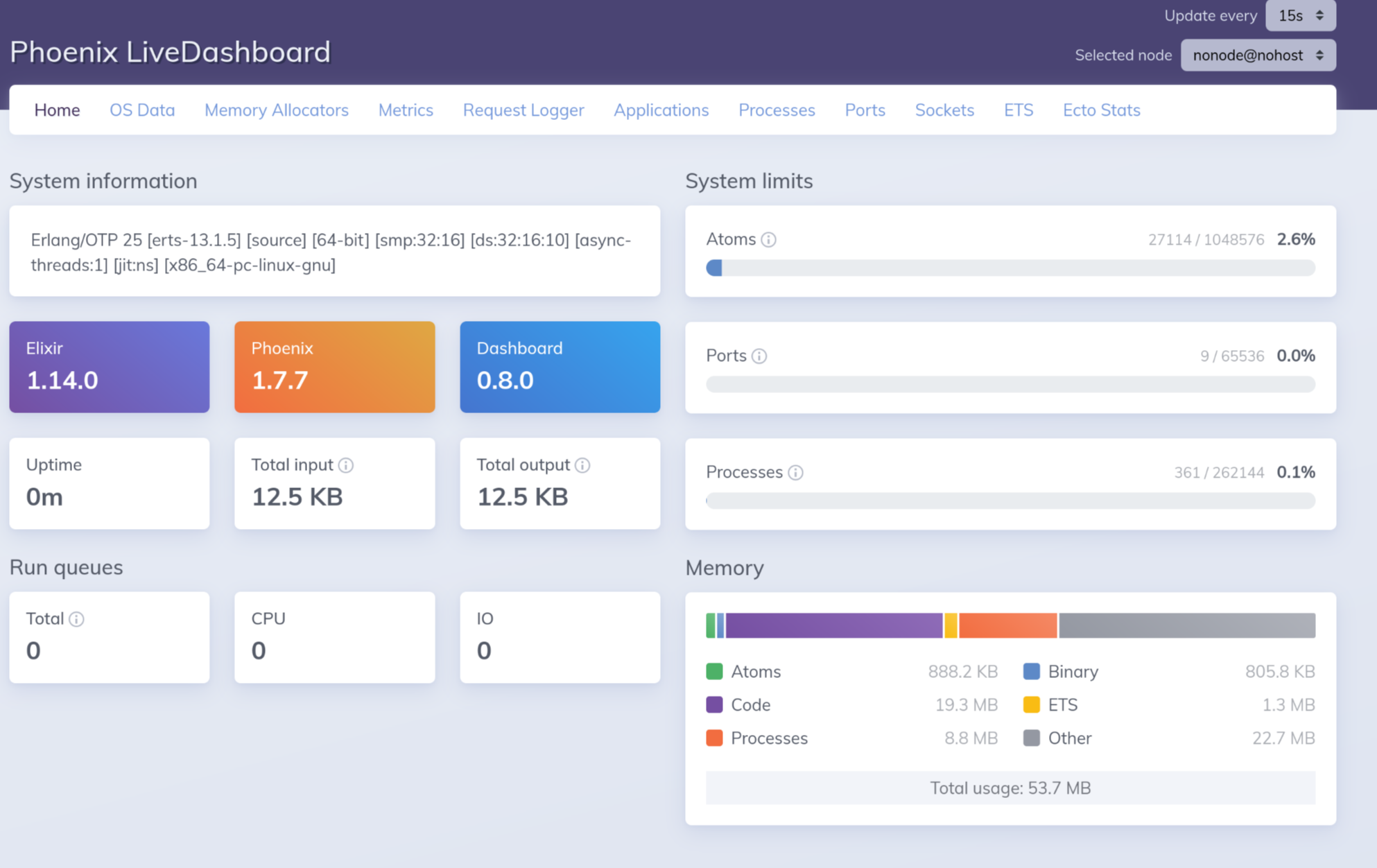

Live dashboard! Start the default server config in dev mode and

navigate to https://localhost:4000/dev/dashboard and you

get a live-updating status view of what’s going on with your server.

It’s… well. Pretty good, but it doesn’t quite blow me away

compared to say, Grafana plus any of a plethora of system-monitoring

tools. You can poke around in different areas to get graphs and

statistics of memory, performance, request info, etc. But the graphs

don’t seem to store data persistently, just stream it to your browser –

every time I load the page I get the graphs starting over from 0. I

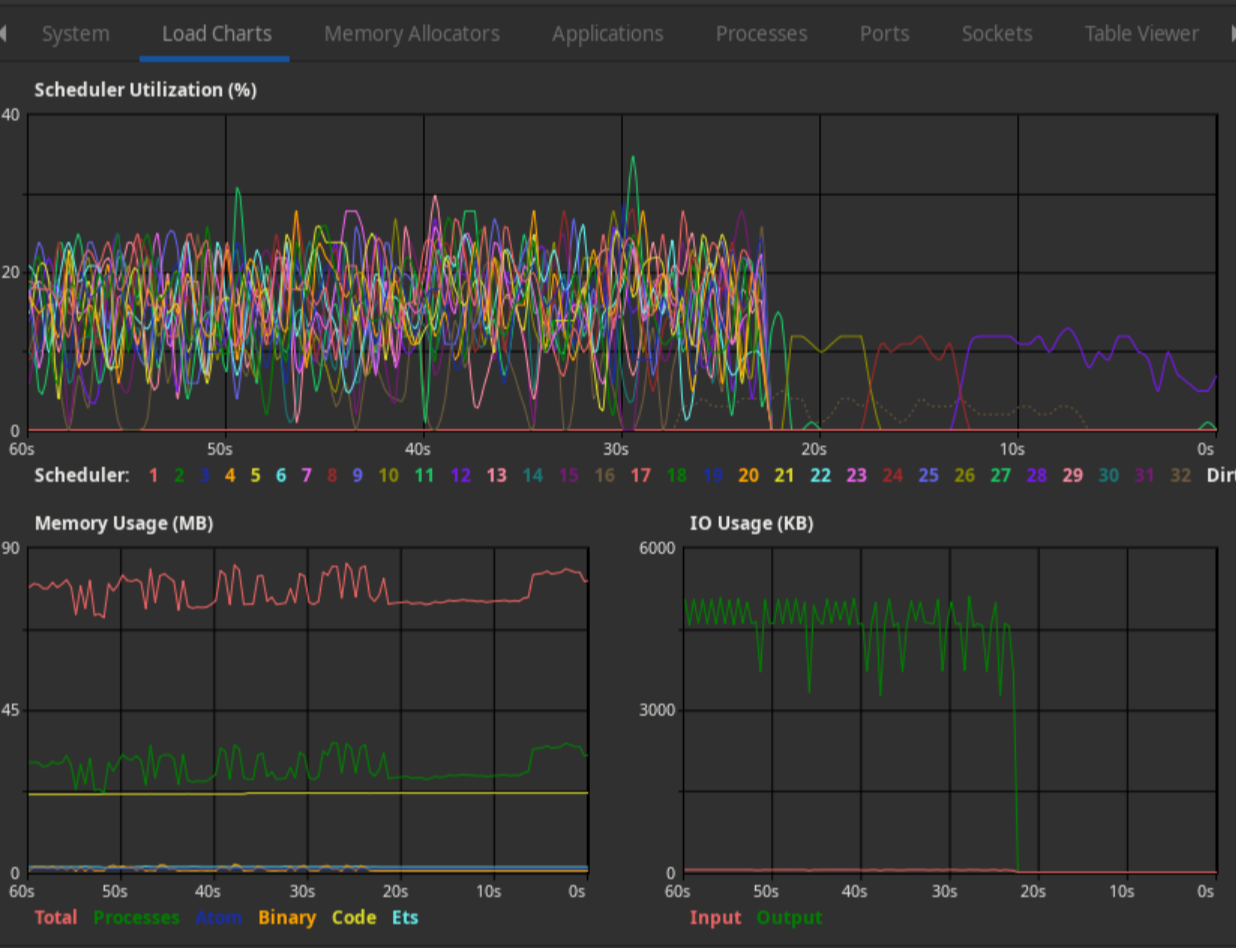

think I would usually prefer the Erlang

Solutions observer started with

:observer.start:

The desktop app just gets me more data, more conveniently. However, the Phoenix dashboard has the advantages that it’s trivial to turn on (at least in dev mode running locally-only), and it has Phoenix-specific stuff that the observer lacks: how much time requests spend in each stage of your app, how many errors have been caused, a page for database integration that I couldn’t get working, stuff like that. Plus a few things on the Phoenix dashboard have nicer and easier-to-absorb presentations, like the ETS table data. I expect that both of them have ten million hooks and plugins available, but I’d also expect the Phoenix ones to be better documented and easier to hack around with. Worth exploring, but both of them are really debugging tools rather than service-monitoring tools, and the desktop one seems

notes

The Elixir and Phoenix docs are… very “do as I say, not as I do”. The

section on macros says “make macros and DSL’s sparingly”. Meanwhile all

of Phoenix is a DSL made of macros. The section on use says

“try to avoid requiring use when you can”. Meanwhile all of

Phoenix involves use to implement its DSL.

OTOH, Rust has this problem too; the stdlib is filled with structures that contain lifetimes, when really this is almost never what you actually want.

You CAN upload multiple files, but it doesn’t give you all of them

unless your input element name ends in [], like so:

<input type="file" name="file[]" multiple />. If you

don’t do that it will upload all the files correctly, but only hand you

the actual file info for one of them in your controller function. I

spent two hours trying to figure out what is going on, down to digging

through the source code, and afaict this is documented nowhere. I still

can’t find for sure in the source where this shit is actually

parsed.

CSRF protection is included by default, and is Magical. My app

mentions it nowhere and it’s still there, pulled in by… something else.

This isn’t a huge problem, because it’s fairly obvious what’s

going on (if you have heard of CSRF protection before) and it the

default project template does include an example of how to use it, if

only by coincidence. But it violates my No Magic rule. (Oh, it’s the

:protect_from_forgery plug, which is totally what you will

find when you grep your project for CSRF or

_csrf_token. Whatever, naming shit is hard.)

The docs for toplevel Phoenix and such are quite good, but once you

go down a level or two into something like phoenix_html or

such it became far more bare-bones. Lots of docs explain what things

are, and semi-often how to use them, but it never

explains how they work. So when you need to try to compose

things, figure out how to build something novel or hack away the weeds

to get to what is actually going on, then you don’t have much of a

map.

I have very mixed feelings about LiveView, and even more

about the built-in components. Being able to define functions that

generate HEEx templates and stick them inline in your HTML pages is

pretty baller. But you quickly end up about 2.5 DSL’s deep – HEEx

templates give <%= => expressions, then components

give you <.contact name={"Genevieve"} age={34} />

expressions, and defining a new component involves learning some new

macros to give it what is, essentially, a function signature. You guys

are going a bit hard here; we already have a tool in Elixir for defining

function signatures, it’s called function signatures.

Also LiveView and components seem to be very tied together when they really don’t have to be. Components are just HTML templates. LiveView is this whole system that runs the HTML templates server-side and then schleps (a diff of?) the result to the web browser over Websockets to stick the HTML into the DOM, schleps client-side events like button clicks or form submissions off to the server to be handled via the same websocket, and probably other stuff I am not aware of. So you never need to really deal with writing Javascript as far as I can tell, you just have a single JS file you plop into your site that sets up the websocket and implements the LiveView protocol, and from then on it just does whatever the server tells it to. Technically this sounds like it has some very interesting tradeoffs vs. the traditional approach of client-side JS app + HTTP API, but I am so unqualified to even try to comment on it. Pro’s: stateful, more work done on server rather than client, everything goes through this one websocket. Con’s: stateful, more work done on server rather than client, everything goes through this one websocket. Discuss amongst yourselves.

It’s honestly pretty cool… if that’s what you want. For this case

it’s not what I want, what I want is to be able to use the heckin

website in lynx. Disentangling the bits of LiveView

Example, straight from the docs:

<.unordered_list :let={fruit} entries={~w(apples bananas cherries)}>

I like <%= fruit %>!

</.unordered_list>Renders the following HTML:

<ul>

<li>I like apples!</li>

<li>I like bananas!</li>

<li>I like cherries!</li>

</ul>Honestly, pretty baller, but does it need to be its own component rather than a list comprehension in HEEx?

<ul>

<%= for fruit <- ["apples", "bananas", "cherries"] do %>

<li>I like <%= fruit =>!</li>

<%= end =>

</ul>Or even just:

<%= unordered_list("I like %s!", ["apples", "bananas", "cherries"]) %>The answer is… well, sometimes. If you’re building a big application

with a complicated UI, then you probably really do want a single list

function so you can customize it however you want. But again, I’m really

not convinced we need another heckin’ DSL for it. It Looks Like

HTML, which is nice for editors and such, but now your component code

consists of foo and @foo and

{foo} and augh I just cannot be fucking arsed with it. I

want to generate a fucking form, how many fucking layers do I need to do

that? From trying to read the incomplete docs for Phoenix.HTML.Form,

the answer is “at least 3”.

<%= form_for @changeset, Routes.user_path(@conn, :create), fn f -> %>

Name: <%= text_input f, :name %>

<% end %>GREAT, what the FUCK is @changeset? Where does it come

from? Where does it go? Same for @conn. Same for

Routes.user_path(); is this something that is defined in my

router? Or is it the Controller I want to call? Where is

the user_path() function defined? Why the hell is the last

argument a… callback function that generates HTML? That was the sort of

shit I thought this system was supposed to handle for us; isn’t

everything I write in a HEEx template just a function that

generates HTML?

I got news for you, when I am looking at the function documentation

for the function form_for/4, usually it’s because I want to

know what it does and how it works. “See the module documentation for

examples of using this function” is not very satisfying, but that’s

what it says. Ok, let’s look at the module docs, which say

“form_for/4 expects as first argument any data structure that implements

the Phoenix.HTML.FormData protocol.” Great, so the first param is

something that looks like a map, fine. What’s the second param? DOESN’T

FUCKING TELL YOU. Ok, let’s look at the API docs for

form_for/4. Wait a second, I DID and it didn’t fucking

tell me what the arguments are, that’s why I’m fucking

here! There’s a type signature, but telling me that it is named

action and of type String does not fucking

explain how we go from Routes.user_path(@conn, :create) to

whatever the ass appears in my actual HTML!

jfdskla;fjkdls;afjkldsa;jgkl;sdajkl;fdjgkl;dsjfkl;dsajfkl;jaweei;wiofjkxzl;fjxc;lzjv